In the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, residents can rarely prove they own their home. Aluisio Cantalice is the "go-to man" to broker deals in this informal market

RIO DE JANEIRO - Brazilian lawyer Aluisio Cantalice has an interesting job: brokering sales for real estate that nobody officially owns.

Sitting shirtless and surrounded by untidy stacks of papers, Cantalice works from a sweltering office inside the sprawling favela of Rio das Pedras, on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro.

The shanty town is home to an estimated 170,000 people and when someone decides they want to move, buy or sell their home, even if it was built illegally, the lawyer is their go-to man.

"Most of the property trading is informal - between individuals in the community," Cantalice told the Thomson Reuters Foundation during an interview in his office.

"These kinds of sales are happening frequently," he said, adding there are no official statistics on the number of black market deals in his community, let alone nationwide.

As Brazil prepares for the Olympic Games, millions of the nation's poorest residents continue to occupy homes and land that is not formally documented within the country's already archaic property system.

This means it is difficult for them to prove ownership and they are unable to improve their lot by seeking a bank loan or accessing government services tied to property.

Brazil's favela residents are even more vulnerable when it comes to disputes over land ownership. Most rely on community organizations for protection if their tenure is threatened by local militias or developers.

BOOMING BUSINESS

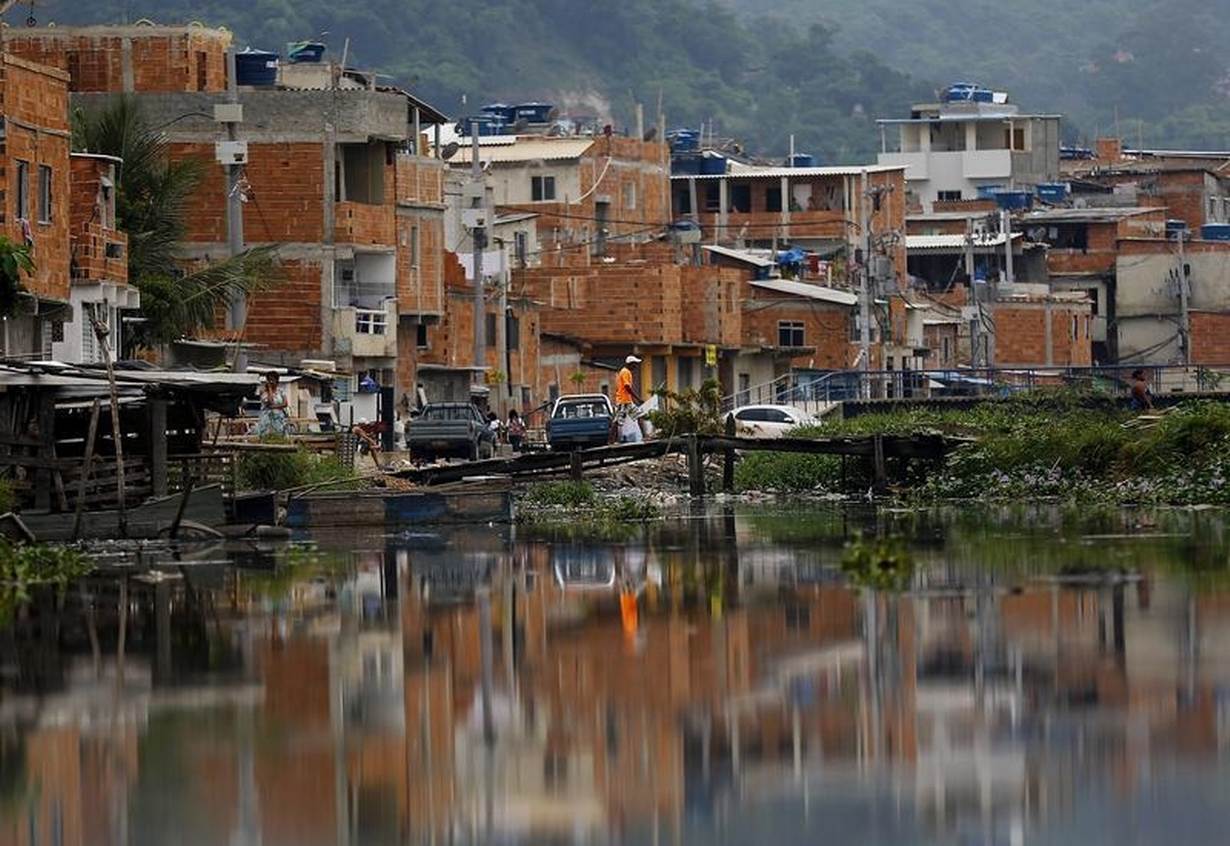

The lack of official deeds has not stopped a brisk business evolving which sees unofficial sales and rental deals being brokered for the thousands of cheap cinderblock homes clinging to the steep hillsides on the peripheries of Rio.

A world away from the golden beaches, shiny new high-rise condominiums and trendy bars showcased on postcards, many residents of Rio das Pedras appear content to negotiate property outside the legal system.

Mistrust of the state has seen the growth of informal networks of family and friends who band together to protect their own property interests.

"Most people do not want formal ownership, as it comes with high bureaucratic costs and few benefits," Cantalice said, echoing the views of other local residents.

The Ministry of Cities, a government department responsible for urban affairs, including the favelas, did not respond to interview requests.

HISTORY OF EXCLUSION

More than one in five of Rio de Janeiro's 6.5 million residents live in favelas, according to government data, including many construction workers, service employees and cleaners who keep business running smoothly.

Densely packed, largely unplanned neighbourhoods of small red brick homes connected by tangled webs of electric wire, favelas often occupy plots of undesirable land surrounding Rio and other Brazilian cities.

Children scamper through narrow alleyways littered with trash as a result of poor public services, and stray dogs search for food in neighbourhoods that are often the only option available in a city where low cost housing is at a premium.

In much of Rio, monthly rents of 7,000 Brazilian reais ($2,000) can rival those in Los Angeles or Toronto while the local minimum wage is 880 reais per month.

The favelas first appeared in Rio in the late 19th century and expanded rapidly in the middle of the 20th century due to increased urbanization.

Many grew from squatter communities created by new arrivals from Brazil's poor northeast who migrated to the city in search of jobs and opportunities.

Following the collapse of Brazil's military dictatorship in 1985, the nation's new constitution of 1988 enshrined a form of tenure or squatter's rights. People who had lived on a plot of land for more than five years received some security against eviction.

These changes, however, did not provide residents with formal ownership.

"Favela residents often don't have title, but they have rights," said Desmond Arias, a public policy professor at George Mason University in the United States, who studies Brazil.

"A lot of residents are reluctant to obtain title because they will have to pay taxes," he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

In some communities, the residents' association acts as an informal moderator of deals, he said.

In others, particularly in favelas dominated by militia groups, such as Rio das Pedras, gangs play a prominent role controlling the market, Arias said.

EXTORTION ANXIETY

João and Juliana, the owners of a roadside restaurant in Rio das Pedras, have first hand experience with these problems.

The couple, in their mid thirties, bought their small restaurant from another local business person in an informal trade.

They did not seek the help of a lawyer or government officials and secured the deal without paying property taxes.

While this is common within the favela communities, it also exposes residents to exploitation.

"There's intimidation from the militia," João told the Thomson Reuters Foundation without providing his last name, fearing reprisals.

"All of the store owners must pay a 'security tax' of 25 reais per week."

Business owners who refuse to pay face robbery by masked men, or having their stores destroyed, he added.

Some residents view the militia and its leaders as Robin Hood like figures, protecting the poor and marginalized when no-one else will, he said.

But João does not see it that way.

"I don't like the current system (of informal ownership), he said. "We don't have autonomy to seek benefits from our property."

"But to resolve it would take a lot of work, and spending money we don't have," Juliana said.

The couple estimate that it would cost around 10,000 reais to gain formal title to their property.

This would include the bill an architect would charge to prepare a ground plan of their home - built on land informally owned by Juliana's grandmother - and the cost for lawyers and taxation to formalise their documentation.

"All of these problems (a lack of formal title, the militia's power and little formal presence of the state) are connected," Juliana said.

GOVERNANCE QUESTIONS

Inside the sparse office of the favela's community council, the elected body which acts as a de facto municipal government, Alexandre Pedro says residents have learned to live without much of a relationship with the state, including a lack of formal property ownership.

But that does not mean they are happy about it.

"About 80 percent of the problems here would be fixed if the state provided basic services," Pedro, the council's vice president, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Garbage collection service is poor and there are not enough elementary school places for the children of new arrivals to the community.

Brazil's recession, described as the worst since the 1930s, has hit local residents hard, Pedro added.

Despite job losses, the community's population has still grown by about 25,000 over the past five years. Attempts by the community council to track who owns which plot of land have not borne fruit.

"The buildings are going up so fast," he said. "Prices in the informal market have risen by about one third."

This burgeoning demand for property has fuelled a brisk business for brokers like Cantalice who also acts as a de facto mediator for disputes between families and neighbors over increasingly lucrative land and houses.

"When I am called to resolve a dispute, I try and get documents such as identification cards or electricity bills to help resolve the case," Cantalice said, leaning back on his swivel chair while his children study at an adjacent desk.

In most cases, favela residents are able to obtain power bills directly from the electricity company to help ascertain their claim to their home, he said.

Proof of formal connection to water mains, however, is far more difficult to obtain as many residents siphon it directly from city pipes to avoid paying bills.

After years of dealing with the informal market, favela residents and lawyers say it may not be ideal but they are used to it.

"The system in Brazil is rather perverse," Cantalice said.

($1 = 3.49 Brazilian real) (Reporting By Chris Arsenault Editing by Paola Totaro; Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking and climate change. Visit news.trust.org)

For more on land and property rights visit our new website place.trust.org

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.