Footballer Keita Balde intervened to help solve the decades-old plight of migrant fruit-pickers sleeping rough

By Sophie Davies

BARCELONA, June 24 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - A professional footballer's campaign to provide shelter for homeless African fruitpickers has exposed the decades-long plight of Black migrant farmworkers in Spain, according to human rights activists.

Monaco winger Keita Balde, born in Spain to Senegalese parents, started paying for food and hotel rooms for about 80 seasonal workers this month on hearing about them sleeping rough in Catalonia, the wealthy northeastern region where he grew up.

Balde, 25, said in an Instagram livestream "nobody deserves that kind of indifference in their lives. It is very ugly".

Yet seasonal migrant workers sleeping rough is nothing new, with thousands left homeless in Spain every year because of racist prejudice, according to activists.

"It has been happening [in Lleida] for more than 25 years – it is a situation that is repeated year after year," said independent anti-racism activist Nogay Ndiaye, who partnered with Balde to find accommodation for the fruitpickers.

"Every day from May until September, every year, it's like Groundhog Day with people sleeping on the street ... It's extremely difficult for a non-white person find somewhere to stay in this town," she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

About 25,000 migrants from Africa, Latin America and Eastern Europe arrive each year for harvesting season in Lleida, a fruit-growing region that produces apples, pears and peaches.

Many have been in Spain for years, hopping from province to province in time for each harvesting season.

But Ndiaye, who was born in Lleida to a Spanish mother and Senegalese father, said the situation was worse this year with about 2,000 seasonal workers sleeping rough in the province.

Unemployment in tourism and other sectors due to the coronavirus pandemic has resulted in more people arriving in pursuit of agricultural work, one of the few industries allowed to keep working during the lockdown.

Balde wanted to help 200 migrant workers but only two hotels were willing to help, said Ndiaye.

Balde was not available for further comment.

"I'm non-white and I work for the state as a teacher, but I have many problems when I want to rent a house," said Ndiaye.

EMERGENCY BEDS

Gemma Casal, spokeswoman for Fruita amb Justicia Social, a local farmworkers' activist group, said a lack of housing was not the issue.

"Here nobody will rent a flat to seasonal workers ... but there are towns that have loads of empty flats," she said.

Farmworkers across Spain face the same, often illegal, situation, she said, even though farm owners are obliged by law to offer accommodation to those who have travelled more than 75 km (46 miles) to work for them.

Spain's Ministry of Labour and Lleida City Council were not available for comment.

Lleida City Council announced earlier this month that it would provide emergency accommodation for up to 150 homeless workers in a pavilion at a convention centre.

Undocumented migrants without a work visa, as well as those who have newly arrived and not yet found work, can use the emergency accommodation for up to 10 nights, the council said.

It also launched a new census device in collaboration with local agricultural organisations, aimed at having real-time data on seasonal workers and their accommodation status.

Casal welcomed the accommodation but as a temporary fix, calling for public units where farmers could hire beds for workers.

"When there have been people sleeping in the streets for 30 years you can't respond with the emergency opening of a pavilion ... but at least they've opened this space," she said.

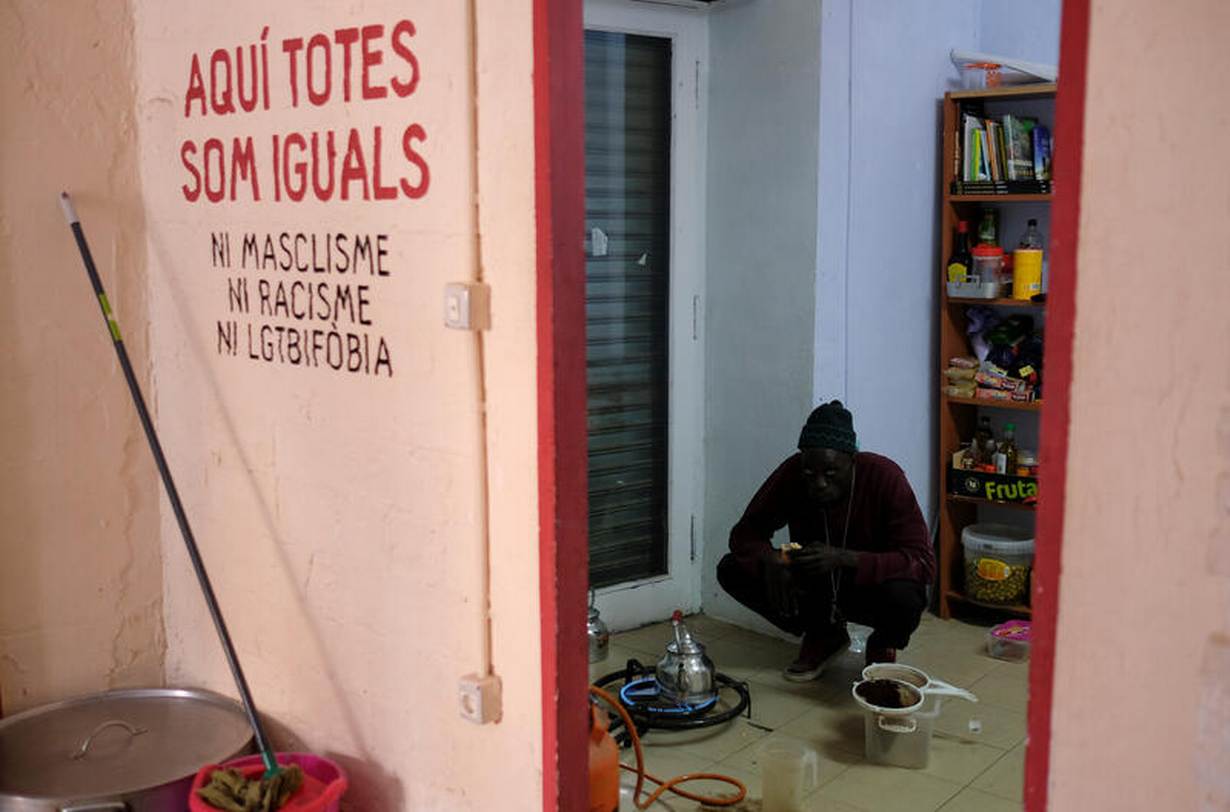

CRAMPED SHELTERS

The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights warned last year that some migrant farmworkers were "forced to live in conditions barely fit for animals".

Its 2014 report into Spanish labour exploitation found that agriculture was the economic sector where the most "severe forms of exploitation are most likely to occur, especially in jobs related to fruit-growing".

Human rights groups have flagged dire living conditions as long rife in the hot, dusty southern province of Almeria, where more than half Europe's fruit and vegetables are grown.

Many migrant workers live in cramped, improvised shelters near the greenhouses where they work, said Clare Carlile, a researcher at British charity Ethical Consumer.

"These very, very poor living conditions have persisted for 20 years," she said.

Lengthy waits for work permits were also part of the problem, said Casal, which could take five years to obtain.

"It's important the Spanish state regularise the migrant workers ... they can't work in a clandestine way for years," she said.

Related stories:

Migrant workers face cruel summer as COVID-19 batters European tourism

Europe's new jobless urged to pick fruit amid huge farm labour shortage

Spain provides lockdown support for trafficking victims, prostitutes

(Reporting by Sophie Davies; Editing by Belinda Goldsmith Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, which covers the lives of people around the world who struggle to live freely or fairly. Visit http://news.trust.org)

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.